by Andy Green

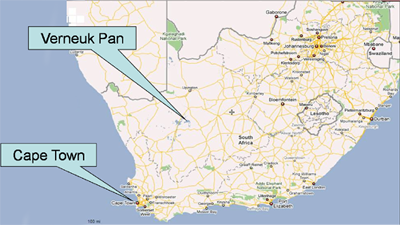

I went out to look at Verneuk Pan, South Africa, in November of last year, concluding that it would take a truly huge amount of work to clear all the stones and prepare the track. However, 2 things made another look worthwhile. The first was discovering that Australia’s salt lakes are wet more often than we’d thought, so they may not be the perfect southern hemisphere site. The second was that Richard Noble and I would be in South Africa together for a couple of days, attending a dinner to commemorate Alex Henshaw’s record-breaking flights in 1939 to Cape Town and back.

Verneuk is over 300 miles from Cape Town, and we only had one day to spare, so this was going to be tight. Fortunately for us, the terrific South African friendliness and hospitality came to the rescue, with Jannie van Wyck (organiser of one the dinners that we attended) offering to fly us up there in his Cessna 210. Better still, he arranged for us to use 2 aircraft, the second being a Scout which was designed to land on places like Verneuk Pan – if anything could get us there, the Scout would do it.

Left: South Africa: Verneuk Pan is over 300 miles from Cape Town

Left: South Africa: Verneuk Pan is over 300 miles from Cape Town

The weather did its best to defeat us, with a lot of rain on the Pan a couple of days before we set off. This turned out to be a blessing, as it gave us a chance to see how the surface dried, which was impressively quickly. Three days after heavy rain, we were landing aircraft on a hard, dry surface – quick drying is an ideal characteristic for a land speed record site.

Images below: Johan (one of the most remarkable pilots I’ve ever flown with) and I land on the Pan in his Scout, only 3 days after it had rained.

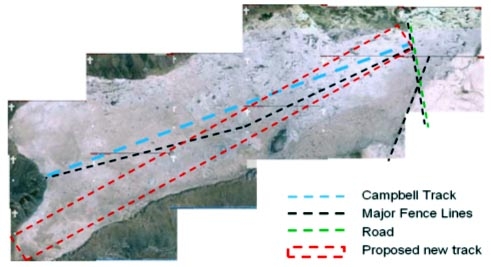

Since my last visit in November, I’ve spent a lot of time looking at other options for Verneuk. Bearing in mind that we’re looking for a 10 mile track with some over-runs (so about 12 miles total), we can get almost 12 miles if we go diagonally across the old 1929 Campbell track:

|

This was the area that we needed to survey – because of the fence lines, I had only seen the northern part of the Pan last November. With Johan Ferreira’s Scout now at my disposal, together with his extraordinary flying skills, fences were no longer a problem – we could go anywhere!

Fence lines like the one on the left of the picture were no problem for the Scout – it’s the mounds of black stones in the background that we’re worried about!

Fence lines like the one on the left of the picture were no problem for the Scout – it’s the mounds of black stones in the background that we’re worried about!

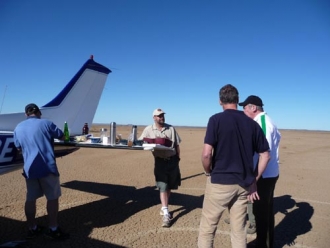

While the Scout was definitely the go-anywhere plane, being half the weight of the Cessna, it was also a lot slower, so Johan and I set off at dawn to reach the Pan, while the others enjoyed a leisurely coffee. The flights were timed to perfection, with Scout and Cessna arriving together at Verneuk, at which point the South Africans showed us how Sunday morning breakfast should be done.

Jannie, Johan, Andy and Richard discuss the morning’s survey work over breakfast on Verneuk Pan

Jannie, Johan, Andy and Richard discuss the morning’s survey work over breakfast on Verneuk Pan

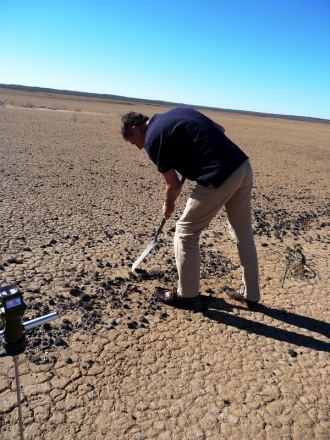

Breakfast over, we started the long process of aerial survey and multiple landings, taking readings and checking the stone deposits at a number of places along the track. The whole Pan is remarkably and consistently hard, which is just what we’re looking for – while the minimum hardness measured with the cone penetrometer is a Cone Index (CI) of about 150, Verneuk was giving CI readings of 300, with some places over 350: all the more remarkable given that the Pan was wet 3 days earlier.

We took hardness readings and checked the depth of the stones along the track.

So what the final result? Much the same as before – this could be the best Land Speed Record track in the world, but it’s going to take an awful lot of work to make it so. At least now we’ve got more confidence in how good it could be and how much work is involved.

So what the final result? Much the same as before – this could be the best Land Speed Record track in the world, but it’s going to take an awful lot of work to make it so. At least now we’ve got more confidence in how good it could be and how much work is involved.

With no other major sites to visit, we’re nearing the end of this long desert research programme. It’s time to weigh up all the factors and choose the desert(s) where we want to run BLOODHOUND.

Looking out over Verneuk Pan – with enough work, this could be a great place to run BLOODHOUND.

Looking out over Verneuk Pan – with enough work, this could be a great place to run BLOODHOUND.