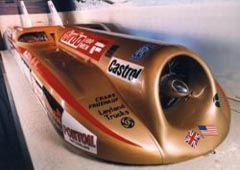

Richard Noble started the Thrust2 project with a dream, zero credibility, a mountain of determination – and £175.

Richard Noble started the Thrust2 project with a dream, zero credibility, a mountain of determination – and £175.

The dream was to bring the Land Speed Record back to Britain.

The money came from the sale of the wreckage of his first jet-engined car, the crude, self-designed Thrust1, which he had just crashed at RAF Fairford in 1977.

Most people would have been discouraged after such an accident, which was caused by a seized wheel bearing and, thankful to have survived, would have moved on to quieter things. Noble moved on – to the creation of a car that would meet all manner of adversity on its way to ultimate success a quarter of a century ago.

He used the meager funding to purchase a Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet engine, and launched his latest project – Thrust2 – at the 1977 Motorfair at London’s Earls Court. He had just that massive power unit to show startled visitors, and his dream to regale them with.

Later, when he advertised for a designer capable of creating a 650 mph car, Fate put him together with fellow countryman John Ackroyd. The latter went to work in a derelict cottage on the Isle of Wight. His company car was his trusty old Hercules pushbike. Glamour was irrelevant. Practicality and progress were all that counted as Ackroyd laboured away while Noble scoured the country for financial support.

In 1981 they finally got to the hallowed salt flats at Bonneville, in Utah, US. There, rookie Noble encountered a series of frights running on metal wheels on the salt surface. Eventually he was able to make one 400 mph run using the afterburner, and discovered that Thrust2 became more stable the more power he used. The next day the rain came and shut down the project for the year.

As one sponsor put it: “Richard, you promised us gold and came back with bronze…”

In August 1982 Noble made a small error of judgement during a test run in the UK and damaged the car; after a frantic rebuild the team got to Bonneville only to encounter flooding. After a desperate search for an alternative venue, it relocated to the Black Rock Desert in Nevada, and there, finally, Thrust2 approached speeds of 600 mph before the weather gods intervened again.

1983 marked the project’s last chance, and after another series of tribulations and cliffhangers Noble finally succeeded. On October 4 he drove Thrust2 to an average of 633.468 mph to erase America’s grip on a record once thought to be the exclusive province of the British.

1983 marked the project’s last chance, and after another series of tribulations and cliffhangers Noble finally succeeded. On October 4 he drove Thrust2 to an average of 633.468 mph to erase America’s grip on a record once thought to be the exclusive province of the British.

The Thrust2 story was no fairy tale. Instead, it was the product of opportunism, determination, and a relentless refusal to give up in the face of adversity.

“The programme succeeded because everybody worked together as a team,” says Glynne Bowsher, at that time a Lucas Girling engineer who designed the car’s brakes.

And it was that teamwork and camaraderie - that union between the men and women who came to share and believe in Noble’s dream - that saw the tight-knit little group through all of the trials that separated it from the ultimate goal.

David Tremayne