Competition is the greatest spur to progress. And when, during a visit to Bonneville in October 1990 Richard Noble learned that the great American speed king Craig Breedlove was planning to attack his Thrust2 record, he reacted in the only way he knew. He would fight back.

Breedlove was already well advanced with his beautiful jet-powered Spirit of America – Sonic 1 when Noble first sowed the seeds that would blossom into ThrustSSC. The name of the new car said it all - it stood for SuperSonic Car. To Noble, it was clear where Breedlove was headed, and that their battle would take one of them through the Sound Barrier on land. In order to catch up, the British had to put in five man/hours to every one of the Americans’.

Once again Noble had to fight apathy born of lack of corporate courage. “We virtually had to fight Britain,” he remembers.

Inevitably ThrustSSC was every bit as opportunist as Thrust2. But where Noble’s original programme had primarily refined existing concepts due to financial imperative and practicality, this one had to be ground-breaking. Nobody had ever created a supersonic car.

It thus underscored time and again the crucial importance of impeccable technical research and engineering. There were no supersonic wind tunnels that could produce meaningful data for a vehicle running at such enormous speeds at ground level. Aerodynamicist Ron Ayers, whose skill would be the cornerstone upon which the programme was built, was confident that computational fluid dynamics (CFD) could supply the data he demanded, but there had to be an alternate source by which to compare and validate it. Such was the magnitude of the task that nobody was going to start building a record contender unless they were totally convinced that the attempt could be made with apposite levels of safety.

It thus underscored time and again the crucial importance of impeccable technical research and engineering. There were no supersonic wind tunnels that could produce meaningful data for a vehicle running at such enormous speeds at ground level. Aerodynamicist Ron Ayers, whose skill would be the cornerstone upon which the programme was built, was confident that computational fluid dynamics (CFD) could supply the data he demanded, but there had to be an alternate source by which to compare and validate it. Such was the magnitude of the task that nobody was going to start building a record contender unless they were totally convinced that the attempt could be made with apposite levels of safety.

The aerodynamic forces involved were so colossal that any accident was likely to be fatal.

Ayers and Noble hit on the idea of running a one twenty fifth scale model at very high speeds on a rocket-powered railway at Pendine in Wales. When the data from that was compared with the CFD data, the correlation was within acceptable limits. They had a project.

That was but one of the technical problems that had to be researched and conquered. Another was the unique rear-wheel steering necessitated by ThrustSSC’s unusual layout. This time they modified an ordinary Mini, to prove that the concept could work.

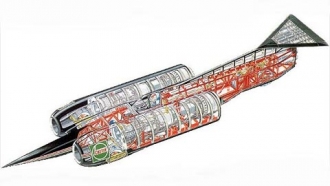

Then there was the use of two engines, giant 20,000 lb Rolls-Royce Speys. The finished ThrustSSC was a vast black brute that looked like nothing else that had ever been aimed at the record, with its slim fuselage and the engines slung either side of the central cockpit.

Then there was the use of two engines, giant 20,000 lb Rolls-Royce Speys. The finished ThrustSSC was a vast black brute that looked like nothing else that had ever been aimed at the record, with its slim fuselage and the engines slung either side of the central cockpit.

As ever myriad technical, financial, operational and weather problems had to be overcome before Andy Green finally made history by breaching the Sound Barrier at 763.035 mph on Black Rock Desert on October 15 1997.

The success validated not just the value of romantic notions such as dreams and a spirit of adventure, but the limitless power of applied engineering and technology.

“I was accosted by a policeman at the House of Commons this year,” Noble recalls. “‘You Richard Noble?’ ‘Er yes – am I in trouble?’ ‘No I want to shake your hand – as a result of ThrustSSC my son decided to become an engineer!’ True story!”

In its own realm, ThrustSSC’s achievement was every bit as inspirational historically and philosophically as the first ascent of Everest.

In its own realm, ThrustSSC’s achievement was every bit as inspirational historically and philosophically as the first ascent of Everest.

Visit the Thrust SSC website.