by Hywel Vaughan.

It has been eight months. I have travelled the length and breadth of the country, designed rigs that have been to South Africa, designed leaflets and event stands and even done some decorating, but now I am doing something completely different. With the control systems coming together exceptionally quickly, I have been set the challenge of designing, building and testing a part of the car.

I have set about building a steering wheel for a 1000mph vehicle.

How though does one go about constructing a steering wheel suitable for Mach 1.4? With the high requirements of BLOODHOUND and the intense atmosphere that envelops it, obviously we can't just go out and buy a second hand column off an old Ford Fiesta. Instead we have to develop something that meets the precise and often exigent specification that we have set ourselves.

This steering wheel will be moulded to Andy's hands, making sure that he is in complete control and doesn't have to look around for buttons - after all, when you are doing a mile in 3.5 seconds you can't afford to wait a few seconds to fire the parachutes. Before we even get as far as the moulding though, we must undertake that inevitable task that comes with any form of design work; whether it be in secondary school design technology or in the most sophisticated engineering project - research.

Where do you look though? Like a lot of this project, there is very little precedent in supersonic steering wheels. Well, we must look at what has worked, what hasn't worked, and what is working now. Firstly, we must look backwards.

Back in 1997, Thrust SSC used an aircraft yoke manufactured by Page Aerospace. With the very kind permission of the people at Coventry Transport Museum, I was granted access to the cockpit of the Land Speed Record holder itself. I got to sit in the seat that Andy had been in when he drove through sound, and I got to grab the steering wheel. What struck me the most about this was its size.

Back in 1997, Thrust SSC used an aircraft yoke manufactured by Page Aerospace. With the very kind permission of the people at Coventry Transport Museum, I was granted access to the cockpit of the Land Speed Record holder itself. I got to sit in the seat that Andy had been in when he drove through sound, and I got to grab the steering wheel. What struck me the most about this was its size.

As you can see from the picture, the steering wheel fits my hands perfectly. 'Great!' you might think, 'you can use that!', but I can tell you now that I have seen the size of Andy's hands, and they are a great deal bigger than mine. And I have what I consider average size hands. Discussing this with Wing Commander Green though, he said that although the wheel wasn't perfect, the layout of the wheel and raised guards on the buttons were exceptionally useful, and something we should incorporate into BLOODHOUND.

As you can see from the picture, the steering wheel fits my hands perfectly. 'Great!' you might think, 'you can use that!', but I can tell you now that I have seen the size of Andy's hands, and they are a great deal bigger than mine. And I have what I consider average size hands. Discussing this with Wing Commander Green though, he said that although the wheel wasn't perfect, the layout of the wheel and raised guards on the buttons were exceptionally useful, and something we should incorporate into BLOODHOUND.

JCB Dieselmax went for a completely different approach.

JCB Dieselmax went for a completely different approach.

Following the more 'traditional' approach to racing steering, the setup is similar to that used on a modern day F1 car. The buttons are all positioned on the centre of the steering wheel. Now, if you place your hands in front of you and imagine you are holding your steering wheel at the 'quarter-to-three' position, then try placing your thumbs in the centre, you will feel just how unnatural that position is. Under high pressure, the last thing you want to be doing is having unnecessary forces exerted on your thumbs. What is much more natural is to have your thumbs in the 'thumbs up' position - like a joystick. So let's talk about joysticks.

There are a wide range of joysticks out there that deal with a range of functions; from flight simulator gaming on your PC to HOTAS systems in fighter jets. All of them though have something in common - they are designed to be ergonomically comfortable. They have been painstakingly designed to fit into your hand so you get the most control out of the least physical input. What is important there though is that they have been designed for your hands, and for my hands, and for several thousand other people's hands. BLOODHOUND SSC is a one man only machine, so we can't just take two joysticks and join them together to make a yoke. What we can do though is look at their configurations and come up with some concepts from them. So that is what I did.

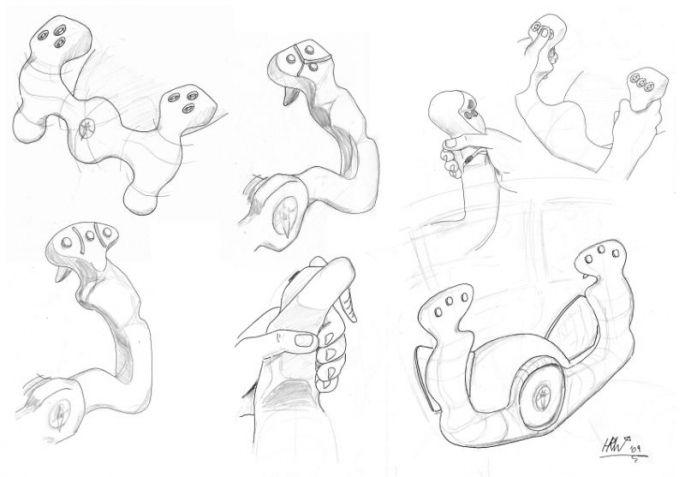

Working in parallel with pencil and blue foam (pictures top of the page and right), several rough and ready configurations for the steering wheel were created. Obviously these had to modelled to my hands rather than to Andy's - I couldn't exactly take his hands with me - but they give a good enough representation of how we could lay out the steering wheel, how many buttons we could fit in and where, and how we wanted the whole set up to feel.

Working in parallel with pencil and blue foam (pictures top of the page and right), several rough and ready configurations for the steering wheel were created. Obviously these had to modelled to my hands rather than to Andy's - I couldn't exactly take his hands with me - but they give a good enough representation of how we could lay out the steering wheel, how many buttons we could fit in and where, and how we wanted the whole set up to feel.

We can then understand what sort of layout Wing Commander Green wishes for his steering wheel; the foundation of the next stage of the project. From this, we can create a rig that Andy can actually mould to his hands, and that is where the fun really begins.

So what lessons have been learnt from this?

Firstly, talk to your client. In this case my client is Andy Green. The product is for him and him only. What he want, he gets. He is the most valuable source of information for this design.

Secondly, creating physical models is a nice quick way to get a lot of understanding on ergonomics and functionality. They can show an idea quicker than you can explain things, and make a huge difference when human factors are involved.

Finally and most importantly; do your research. It is never the glamorous side of design, especially with a supersonic car, but it is the most valuable. It shapes everything you do, and in modern day design is something so often ignored. It may not be glamorous, but when someone is using your product at 1000mph, it pays to be thorough.