written by Ron Ayers (as Andy is away supporting RAF air operations abroad).

July was another fantastically busy month for the Team and it kicked off with The Goodwood Festival of Speed. This was our third appearance at this unique and massively popular event. We had on display, for the first time, our full rocket propulsion system consisting of a gleaming oxidizer tank, fuel pump, Cosworth CA2010 F1 engine and, of course, Daniel Jubb's mighty hybrid rocket.

Laid out alongside our full sized car replica it brought home to our many visitors both the scale and the complexity of the engineering that will exist underneath the sleek skin. See more here.

Also on display in our Goodwood pavilion was an F1 in Schools race track (picture above). This is an international education programme which sees students form teams to design balsa wood racing cars, which are then launched down a 20m test track using compressed gas. The recently created 'Bloodhound' class frees competitors up to create 'unlimited' designs - much like the real Land Speed Record - and as a result, times have tumbled dramatically to the point where the fastest Bloodhound class car is now twice as quick as its F1-based equivalent (as an aerodynamicist, I'm delighted - but not surprised!)

You can see the F1 racers, and the team at Goodwood, on Cisco Bloodhound TV, our new web TV channel which we also launched in July. We have wanted to do this for three years and thanks to Cisco coming on board as our networking partner, we are now able to take our fans and followers behind the scenes of The Project in an exciting new way. We have our own artist/filmmaker on the team, Stefan Marjoram, formerly a director at Aardman, and he'll be making two films each month to record this 'engineering adventure'. We'll also be inviting people to make their own films which we can show on the channel so do keep an eye on our website.

Goodwood is one of hundreds of outreach events we do each year to inspire and enthuse young people about science, technology, engineering and mathematics. This effort was recognized by The Institution of Engineering Design who awarded our education team a prestigious prize for The Promotion of Design (see Bloodhound Team win the IED award for Promotion of Design).

Goodwood is one of hundreds of outreach events we do each year to inspire and enthuse young people about science, technology, engineering and mathematics. This effort was recognized by The Institution of Engineering Design who awarded our education team a prestigious prize for The Promotion of Design (see Bloodhound Team win the IED award for Promotion of Design).

Meanwhile the intrepid Dave Rowley from our Education team spent much of the month in South Africa, successfully making contact with organisations there that wish to cooperate with us to promote technical education. It will be great to leave an education legacy in that country.

Meanwhile in South Africa, Rudi, our track boss, reports that the stone clearance at Hakskeen Pan is progressing well. There is much to do still, and the first UK volunteers are going out shortly to lend a hand.

An accolade is also due to Daniel Jubb. He and his support team overcame many practical problems, and a very tight time-scale, to organise the firing of a 6 inch rocket on 12th August. The film of the firing was shown on the BBC programme ‘Bang Goes the Theory’. One of the objectives of this firing was to ascertain whether a partially-used fuel grain could be re-ignited. The reason such a test is important is because many test firings are intentionally quite short, leaving a ‘fag-end’ of unburned fuel. Rocket fuel is a major expense, so being able to re-ignite and hence utilise the remainder of the fuel on subsequent runs is clearly good economics. The re-light was successfully achieved. The firing was shown on BBC1 on BGtT on Monday 29th August.

Recently, at the University of the West of England, colleague Dan Johns and I had the pleasure of meeting some astronauts. They were the six strong team that had recently crewed the Discovery shuttle on its final mission to the International Space Station. Their visit to this country was a whistle-stop tour of educational establishments to underline the fundamental importance of studying mathematics and science (an objective that we obviously shared). One thing that interests me is that none of them had started out with the ambition to be an astronaut. Among other careers they had followed were those of helicopter pilot, aerodynamicist and sub-mariner – none of which is directly useful in space. On reflection I realised that such dramatic career changes are not so surprising. After all if I, at the start of my engineering career (in 1950!!), had expressed the ambition to design supersonic cars my careers advisor would have gently guided me towards a secure institution rather than an educational one...

And now for something completely different! On the weekend of August 6th and 7th the Bloodhound Technical Centre was co-host (together with the SS Great Britain and Aardman Productions, our neighbours on the water front) for the Bristol Harbour Festival. The weather was superb and crowds came from far and wide, so the waterfront was packed for the two days. The full scale mock-up of Bloodhound was a centre of attention and the Bloodhound Driving Experience was in constant use. In addition, and to the background accompaniment of sea shanties, the visitors could study Brunel’s great ship, and enjoy watching Wallace and Gromit drive around on their iconic motor-cycle/side car combination, although our own Ian Glover also got in on the act (see right)! Indeed, there was plenty to interest children of all ages.

And now for something completely different! On the weekend of August 6th and 7th the Bloodhound Technical Centre was co-host (together with the SS Great Britain and Aardman Productions, our neighbours on the water front) for the Bristol Harbour Festival. The weather was superb and crowds came from far and wide, so the waterfront was packed for the two days. The full scale mock-up of Bloodhound was a centre of attention and the Bloodhound Driving Experience was in constant use. In addition, and to the background accompaniment of sea shanties, the visitors could study Brunel’s great ship, and enjoy watching Wallace and Gromit drive around on their iconic motor-cycle/side car combination, although our own Ian Glover also got in on the act (see right)! Indeed, there was plenty to interest children of all ages.

Having got my hands on Andy’s diary slot, I am going to take the opportunity to describe some of my own work. As the aerodynamicist on the project I am, of course, concerned with the aerodynamic forces on the vehicle and the way such forces dictate the shape of the car. Articles on aerodynamic topics written by myself, and by Dr Ben Evans of Swansea University, appear in other parts of this web site so I will not repeat them here. However, I am also responsible for the performance of the car, so I will take this opportunity to give some details.

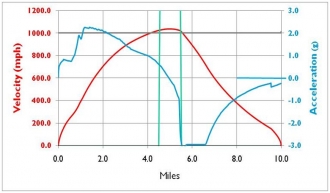

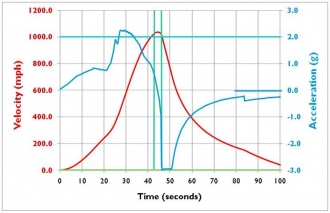

During the design process, aspects of the design are constantly changing. For instance, the predicted weight for the vehicle may change, the aerodynamic drag will also be influenced by detailed changes of vehicle geometry, and predictions of jet thrust and rocket thrust may be updated. It is my job to take all of this information and satisfy myself that the car, as designed, retains the capability to achieve our 1000 mph target. If necessary, I make proposals for improving performance. My computation is done, step-by-step in increments of 1/100 second, on a vast Excel spread sheet. Yes, the same Excel programme that you probably use to record your fuel usage and car mileage, and calculate what expenses you can claim. As you can imagine, my programme is now getting quite large – about 5 megabytes and still growing. Typical graphs are shown below. The vertical green lines near the centre of each graph represent the measured mile.

About six months ago I went further still, and designed the complete run programme for the car, starting with low speed runs, just coasting along a runway to check basic engineering, and culminating in a pair of record-setting runs of over 1000 mph. Why create such a detailed programme more than two years before the car runs? Well, we need it for planning purposes. In particular, to give the first estimates for the following:

How much jet fuel will we consume?

How much solid rocket fuel?

How many tons of HTP?

How long will the run programme take to complete?

What spares will we need?

What experiments will be conducted on each run, so what instrumentation will be required?

Apart from achieving high speeds, we also need to ensure that the car can stop within the distance available. As Andy has pointed out – this is the one operational requirement that is not an optional extra.

This run programme is being constantly updated as the design progresses. When the car is actually running we will be able to compare my performance predictions with what is actually achieved by the car. With some 500 sensors on board we will be able to diagnose how well the car and its individual systems are operating. Such knowledge will enable me to update the programme so that its predictive capability is constantly enhanced. Only when Bloodhound has finished its final run, and the result analysed, will the performance programme be completed.