‘BLOODHOUND is Operational’. In 3 words BLOODHOUND’s Operations Director, Martyn Davidson, summed up the fantastic achievements of our month at Newquay. We had just completed our first public runs, in front of a crowd of 3500 media, sponsors and supporters. We were indeed ‘operational’.

Deploying the Project to Newquay allowed us to start testing the Car at low speed (up to 200mph – which is ‘low speed’ for a Car designed to 1000mph). We also had to train ourselves as a team to operate the world’s most advanced straight-line racing car. One thing we were not going to be short of was power. At the end of September, we completed the static engine ‘tie-down’ tests , demonstrating that the Rolls-Royce jet engine would give us more power in these ‘slow speed’ tests than we had been expecting. Now we had to learn how to control it.

Plenty of power

Plenty of power

The dynamic test profiles were in 8 stages. Profile 1 started using very limited jet power to check the steering and brakes, increasing the power and speed in stages up to Profile 8, the full power 200 mph public runs. Some runs would need to be repeated, so we had perhaps 12-15 runs to develop and test all of the Car’s systems. You can read a summary of how it went in a selection of the test reports .

The first (very pleasant) surprise was just how good the Car felt to drive. Even at the very slow (50mph) speed of Profile 1, everything just felt right . Precise steering response, good brake feel, smooth suspension, the Car was a real pleasure to drive. While Thrust SSC was slightly cumbersome at best, BLOODHOUND SSC immediately felt like a thoroughbred racing car. The BLOODHOUND team is a mix of world-class aerospace and motorsport engineers, and it showed.

Testing and learning

Testing and learning

A slightly less nice surprise was the time it took to bed in the brakes. For runway testing, with very limited stopping distance, we use carbon-carbon disc brakes on all 4 wheels. The problem with carbon brakes is that if you use them very gently, you end up polishing or ‘glazing’ the surfaces and they won’t grip properly. However, to prove the Car’s steering and brakes, we had to start slowly, so a bit of glazing was almost inevitable. It would burn off when we start to go faster…..except that on one of the brakes, it didn’t.

While 3 of the brakes quickly started working well, quickly heating up to their operating temperature (300+ deg C), the front right remained ‘cold’, well below 200C. The solution was to go a bit faster and make the brakes all work harder, so on run 4 we increased the peak speed to 75 mph. The front right remains cold for the next couple of runs, so we bled the brakes again, finding some residual air that had been hiding in there somewhere. Surely that would fix it? No.

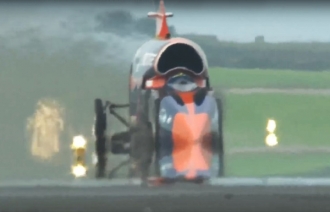

Hot brakes

With plenty of stopping distance available, we tried going a bit faster still, aiming for 100 mph using maximum dry power (max engine revs). Finally, reluctantly, the front right brake burst into life, peaking at 370 deg C and burning off any remaining glaze. It took 8 runs, but finally the brakes were ready. Have a look at this short film clip (right) to see what hot carbon brakes are supposed to look like. With all 4 brakes working properly, we could now find out how fast the Car could safely go on Newquay’s 2744 metre (9003 ft) runway.

While testing the brakes, we had already started to uncover the next surprise, which was the phenomenon of speed ‘overswing’. Jet engines don’t response instantly to throttle changes, so I would have to anticipate a little bit to allow for a small amount of extra acceleration as the engine starts to wind down. The question is, how much would I need to anticipate by?

Back in 1997, Thrust SSC (the car that holds the current World Land Speed Record) used very basic mechanical fuel control systems, so pulling back on the throttle would shut the fuel off, and kill the power, almost immediately. As a result, Thrust SSC’s speed ‘overswing’ was about 10 mph. BLOODHOUND’s EJ200 jet engine is very different, using a ‘fly-by-wire’ digital control system. When my right foot moves the throttle pedal, it sends an electronic request to the jet’s control unit, which decides how quickly it can give me the power I’ve asked for. While the jet acceleration is astonishingly fast, it takes rather longer to slow the jet down again.

Wanting to go fast

Wanting to go fast

For our first max dry power run, I lifted off the throttle at 90 mph, expecting a little bit of ‘overswing’. The speed peaked at 120 mph, which was rather higher than we were expecting. Clearly this was a Car that wanted to go fast. We did 2 more runs at max dry to confirm that the overswing was consistent at 30 mph. It was, so we moved on to using minimum reheat, when the engine puts extra fuel into the jet pipe to ‘re-heat’ the exhaust, giving the distinctive flames and lots more power. The Car was now hitting 150+ mph, which was as fast as we could safely go on the short (one mile) taxiway. It was time for the final test, maximum reheat on the runway, to make sure everything was working for our public demonstrations at the end of the month.

The first max reheat run was done from part-way down the runway, to fit in with Newquay airport’s flight schedules. There was still more than long enough to stop from around 150-160 mph, so I throttled back at 110 mph to make sure that any reheat overswing wouldn’t surprise us. It did. Despite me pulling the throttle back at exactly 110 mph, the speed peaked at …180 mph.

Sharing our ‘Engineering Adventure’

Sharing our ‘Engineering Adventure’

At this point I may have squeaked very slightly, as the far end of the runway was suddenly looking quite close. Quickly onto the brakes, push until the pressure reads 50 bar (no anti-lock system, I have to adjust pressure manually), check the jet engine has wound down to idle, wait for the (still cold) carbon brakes to heat up….. and hope the Car stops in time. It did, comfortably, but this was perhaps the most exciting moment of the test phase. The jet had accelerated our 5-tonne jet car by another 70 mph after I selected the throttle to idle power. At least now we knew what to expect. It was time for our 200 mph public demonstration runs.

With all of the knowledge gained from the above testing, we knew we could do 2 back-to-back runs of the Car within about 15 minutes. For each run, I would drive to the end of the runway, following a pre-determined route round the airfield that would cater for the Car’s huge (250 metre) turn circle. Once lined up and cleared to go, I pushed hard on the brake pedal with my left foot, then eased the throttle pedal down to max dry. Almost immediately the Car started to slide forward, overpowering the brakes. This was the cue for left foot up (brakes off) and right foot smoothly down through the throttle pedal detent (to select reheat).

0-200 in 8 seconds

0-200 in 8 seconds

At 30 mph, max reheat lights up and the Car is accelerating at 30 mph per second. That’s the equivalent of 0-60 mph in 2 seconds, so whatever you have in the garage at home, this is faster. Not bad for a 5-tonne Car designed to cruise at supersonic speeds.

Three-and-a-bit seconds after the reheat lights up, the Car is doing 130 mph and it’s time to throttle back, pause for just over half a second, then smoothly squeeze the brake pedal up to 40 bar as the Car is accelerating through 150 mph, so that by the time the Car hits 200 mph, about 8 seconds after releasing the brakes, the brake are hot and starting to bite. Check the jet engine is still at idle power, increase the brake pressure slightly to 50 bar as the Car starts to slow, watch the brake temperatures climbing up through 500 deg C (they eventually peak close to 1000 deg C), monitor the distance (I can brake slightly harder if I need to), keep the brakes firmly on until the Car is below 50 mph, then ease the pressure off and let the Car roll, looking ahead and left for a disused taxiway that Newquay airport has christened the ‘BLOODHOUND Access Track’ – yes, the Car has its own runway access! Stop briefly by the recovery team for quick check-over, then drive back round the airfield to the end of the runway to do it all again.

All 3 of our ‘public’ days were a huge success. We entertained almost 10,000 people at Cornwall Airport Newquay and for all those that couldn’t make it to Newquay, we ran a live TV show online, including live on-board TV footage from the Car. Half a million people watched live on the day. If you haven’t had a chance to watch it yet, have a look at the runs here, superbly narrated by commentator Mark Werrell and BLOODHOUND’s Chief Engineer Mark Chapman.

BBC and ITV, alone together

BBC and ITV, alone together

We were slightly taken aback by the scale of the media coverage for our first public runs. The interest was overwhelming, with TV crews filming pretty much continuously for over 12 hours, from 6 in the morning as we rolled BLOODHOUND out of the ‘garage’ (should that be kennel?) all the way through to the live evening news coverage. My favourite image of the day was the BBC and ITV live broadcasts for the evening news, both filming their exclusive coverage from a reporter alone in front of the Car…..with the ‘other lot’ just out of frame.

The BBC also did a lot of ‘360 degree’ TV filming with us during the test programme. I started mostly unconvinced by this new fad, partly because they insisted on putting a bulbous 360-degree camera just in front of me in the cockpit while I was driving. However, having seen the final cut, I will admit to being more convinced. I wasn’t the only one, as the 360 film was viewed by well over 1 million people in its first 2 days. If you haven’t seen it yet, have a look at this short video . I’ve never seen coverage of a race car quite like it.

In summary, we achieved what we set out to do. We showed off the Car at 200 mph to the audience at Newquay and, through the media and the live streaming, to a global audience of millions. Perhaps just as importantly, after years of work, we proved to ourselves that we have a Car and a team ready to go much faster. If this year was exciting, then next year is going to be amazing.

Ready for more